Have you seen the toilet paper jokes on Facebook? How about the ones with hoarders and emotional support dogs?

What feels like a hundred lifetimes ago I worked the 11pm to 7am graveyard shift at a local emergency room as the “admitting clerk.” Like it or not, I was a triage person, generally the first to access the “red flag” level of the sick or injured as they trundled into the waiting room. Considering my only qualification for this job was a hot-off-the-press B.A. in Psychology and a pushy nurse mother who got me the job at her hospital…well this whole thing was a frightening prospect. For everyone concerned.

What feels like a hundred lifetimes ago I worked the 11pm to 7am graveyard shift at a local emergency room as the “admitting clerk.” Like it or not, I was a triage person, generally the first to access the “red flag” level of the sick or injured as they trundled into the waiting room. Considering my only qualification for this job was a hot-off-the-press B.A. in Psychology and a pushy nurse mother who got me the job at her hospital…well this whole thing was a frightening prospect. For everyone concerned.

My training was sparse and soon I was let loose at my post. It was a sad gray cubicle where I perched in front of an IBM Selectric typewriter and asked the sick person or anxious family for a mother’s maiden name, social security number and…wait for it…wait for it…medical insurance.

Back then, when the dinosaurs were roaming the streets of Los Angeles, this was a busy hospital ER, but not at night. I arrived at 10:30pm, parked my bicycle in a closet and greeted our skeleton crew: One doc (from a rotating band of crazies), a couple nurses (work hard/play hard types), one orderly who had served in Vietnam as a corpsman and could read an EKG better than the visiting cardiologists, an able and entertaining X-Ray technician. And me.

“What a motley crew” you might say. And you’d be right. But when the ambulances screeched into the driveway with heart attacks, gunshot wounds, car accidents, these blessed professionals jumped into action and turned into heroes. They saved lives, they comforted the loved ones. They took me in at a time when I was lost and floundering.

I joke that I learned more about psychology in my first week working in the ER than I did in four years of college. But this is no joke. For one who is drawn towards self-reflection, this kind of environment is a gift that keeps on giving. And not always in a sugar-coated way.

Because there were so few staff members at night, when the you-know-what hit the fan and we got nailed with a code blue AND other critical patients all at once, the nurses snatched me from my cubicle, pushed me into the treatment room and jammed a clipboard in my hand as they barked out such things as IV line started, patient intubated, this medication, that medication administered. Yes I was the one scribbling down the nursing notes. Me. The future professional musician. At these times our ER turned into an urban Mash Unit and it was all hands-on deck. The pressure to do the work right, even my humble, lowest-on-the-totem-pole job, felt like I was laying my body under a bank vault. And I confess that I loved it.

I saw patients rally, get sent home, to the ICU. Or the morgue. My next job after the ER was performing in a piano bar in an “iffy” neighborhood near downtown Los Angeles. I frequently told my audiences, who consisted of alcoholics and working ladies, that “very little shocks me.”

For example…

I remember watching one of my fellow admitting clerks—a take-no-prisoners kind of gal with a sense of humor as sharp as barbed wire—roll us over with one well-turned phrase. The cops had just brought a belligerent bad guy into the treatment room. He was handcuffed to the gurney and thrashing back and forth. My amazon-tall colleague arrived at his side with her ER forms and asked matter-of-factly “what is your name, sir?”

MOTHER^^^KER !!!

Obviously this was a juicy, bombastic expression of how he was feeling at the moment…and delivered with enough decibels for everyone to hear, even in the waiting room. My friend didn’t flinch, she didn’t look away.

“Sir, is that your FIRST name or your LAST name?”

We could hardly contain ourselves. Or walk back the laughter. Even the bad guy took a breath and shut up. What can you say when you have been disarmed with humor.

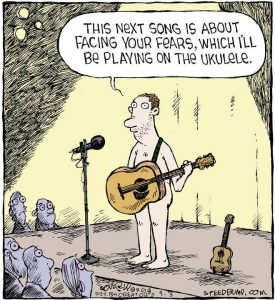

In the ER we called this gallows humor. Merriam-Webster defines it as humor that makes fun of a life-threatening, disastrous, or terrifying situation. I want you to know that this is how we survived some of those long nights. It’s an imperfect coping device. But it mostly works. For awhile.

We would gather in the break room and share the most obnoxious jokes and exquisitely embellished stories. The grosser the better. The work that is done in this pressure cooker can get so intense that, like the pendulum that swings at the Griffith Park Observatory, we have to go to the opposite extreme to “right” ourselves again.

Too bad the break room wasn’t sound proof because our display of frivolity might have seemed crass. In bad taste. At the very least, inappropriate. I remember one quiet night I was keeping watch over the waiting room as some of the staff was guffawing about something. They were very loud. I knew my colleagues were blowing off steam but an angry husband, whose wife was being cared for in the back, rose from his seat in the waiting room, stomped up to me and asked “how can you people laugh like that when patients are sick and dying.” I don’t remember what I said to him. But I do remember feeling awful. Just awful. He was right, of course, and I felt terrible for him. But I also knew that my colleagues were preserving their sanity. The work depended on it.

This is real world Psychology 101: Learning how to make a space in my heart for emotions that pull me in opposite directions. Can I give myself permission to feel it all?

We are in a pandemic right now. I watch the scenes from the emergency rooms flicker across the television and my dusty memories come flooding back. In full technicolor. But this virus is an equal-opportunity fright machine. We are all in this together, living the emergency room life, to one degree or another. Most of us will survive. Others will not.

Having lived that life for real so many years ago, I want to put my money on humor. It got me through then and gets me through now. Sooner or later, we have to laugh a little even as the tears flow.

______________________

Take really good care of yourself and your dear ones!